Atlantic Waves

Audiovisual Network Performance [2002-2007]

Atlantic Waves is an improvisational audiovisual network performance based on a self-written sequencing application. It allows two people to improvise rhythmical music together whilst being in different physical locations.

The idea materialised in 2001 during a coffee break at the NAMM show, when Scott Monteith (also known as Deadbeat), who was working for a software synthesiser manufacturer, and I discussed a simple concept: two people set and delete notes on a step sequencer that is displayed on screen during the performance, allowing the audience to follow the creation of the music in real time.

Following the successful first performance at the MUTEK festival in Montreal in 2002 with me in Berlin and Scott on stage in Montreal, the software was refined and revised multiple times. This allowed for more complex interactions, incorporated a more advanced chat function, and — resulting from a programming error that turned into a feature — introduced a glitch-based destruction of the interface during the performance, synchronised with an equally glitchy deconstruction of the sound.

Remarkable performances included a show at the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in London in 2007, and another at the Centre Pompidou in Paris the same year, both with Torsten Pröfrock (T++) at the Monolake studio in Berlin, as well as a performance with Scott Monteith at his studio in Montreal and me on stage in Bologna, Italy, in 2006.

The Great Matrix

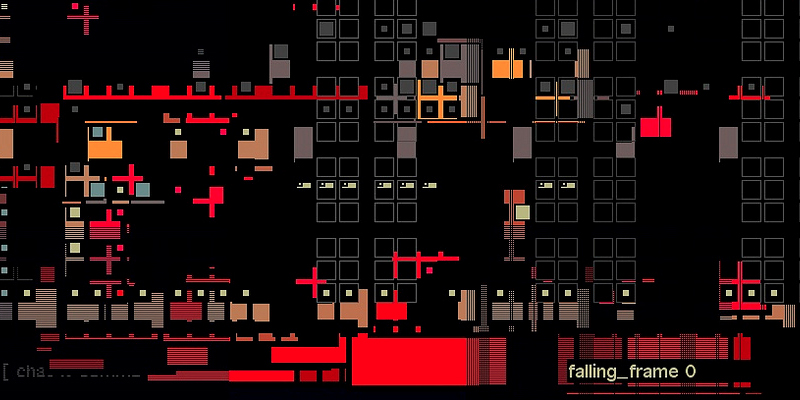

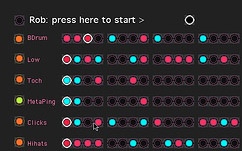

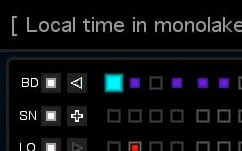

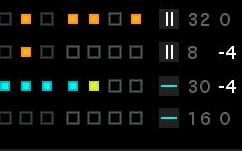

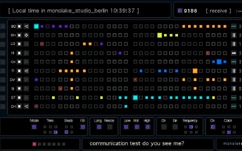

The heart of Atlantic Waves is a step sequencer: a large matrix acting as the score, which can be created and modified in real time by both participants and is projected behind the performer on stage. This sequencer allows notes to be drawn into a grid on screen. The grid consists of 15 rows and 32 columns, providing 15 independent percussive instruments. Each row can be activated and controlled independently.

If a track is active, a red dot moves horizontally through it. Each time this dot hits a coloured square set by one of the performers, a sound is triggered by the audio engine. Each performer has their own colour, making it possible for the audience to follow who is doing what. The movement of the scanning dot can be quite complex: each track can have its own direction, offset, speed, and length, providing a simple yet highly effective way to create constantly permutating musical structures.

Audio

In the first incarnations of Atlantic Waves, the sound consisted of short percussive samples, mostly created by Scott Monteith. In later versions, these samples were replaced by real-time synthesis, allowing more direct access to all sound parameters.

Visualisation

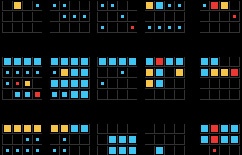

Since Atlantic Waves, Version V, the construction and deconstruction of the image has been an essential part of the performance. At the beginning, the visual structure of the sequencer is created. This is followed by the population and modification of steps within the grid to generate rhythmic movement. Towards the end of the performance, the interface is graphically deconstructed while still in use. These three stages can be repeated or interleaved, as they are all part of the same continuous process.

Network & Software

Atlantic Waves is based on a large MAX/MSP patch. All audio, networking, and visual interaction is handled within this patch. It also contains an embedded chat feature within the graphical interface, allowing the complete interaction between the performers to be followed. The audience receives exactly the same information as the performers.

The software does not transmit any audio or video signals over the network, but only control data. This was an important consideration in 2001, when network connections were sometimes still limited to dial-up modems. Sound and user interfaces are generated simultaneously in both locations, synchronised and controlled by the performers’ commands.

Screenshots show the evolution of the software. It became more and more complex over time, which ultimately also undermined the initial concept: whilst looking cool, it became less and less possible for the audience to understand what they see on screen.